Secrets & Subversion in China: Nu Shu

Ever since civilizations developed written language, it has served as an act of subversion and solidarity for the oppressed and marginalized. Such has been the case for Nu Shu, literally “women’s writing,” the secret written language created by women from the Hunan province in the south of China. Deprived of the right to education, forced to undergo foot-binding and other abuses, and generally viewed as a commodity by the Confucian Han society that entered Hunan from the North, women developed Nu Shu as a way to achieve equality with men, to communicate, sympathize, and support each other.

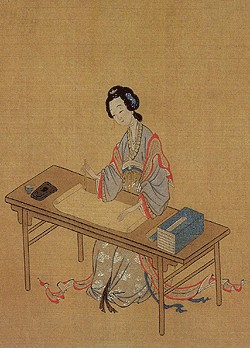

One legend has it that Nu Shu was created by Hu Yuxin, one of the Emperor’s concubines. Lonely at the palace but afraid to bring shame on the Emperor if she wrote of her dissatisfaction, she embroidered it instead. In contrast with standard Chinese writing, Nu Shu characters are syllabic, with only about 600 characters to memorize. They were written as poetry, reading top to bottom or right to left, with seven characters per line. Verses were sung rather than read out loud, and the lines women composed to each other were often very stylized, with popular phrases embroidered into cloth and written on fans and parchments: “Beside a well, one won’t thirst. Beside a sister, one won’t despair.”

A girl well-versed in Nu Shu was viewed as cultured and educated, and was valued more highly on the marriage market. As such, women capable of teaching Nu Shu, either as a private tutor or to groups of four or five girls, were able to earn an independent income in a society where their only other options would be marriage or prostitution.

When a girl first learned Nu Shu, she was often paired with a laotong, or “old same,” another girl of the same age—these girls would go through all the rituals of life together and keep up a lifelong correspondence after marriage. Mothers and sisters would present new brides with san chaoshu, cloth booklets filled with Nu Shu songs and poems wishing her happiness in her new marriage and lamenting her leaving them for her husband’s home. In a feudal society where they were maimed, disenfranchised, and dismissed by men as having nothing important to contribute outside of the home, Nu Shu was a way for women to develop a voice and a bond of sisterhood. Because of this, women from the Hunan province had a much lower suicide rate than women from the rest of China.

In the 1920s women were finally allowed in schools but only Chinese was taught, and Nu Shu was driven further underground. In 1949 the Communist Revolution abolished Nu Shu, viewing it as part of the “old culture,” and during the Cultural Revolution many Nu Shu books—and the women who wrote them—were burned. The Chinese government has since had a renewed interest in preserving the art of Nu Shu, seeing it as an important part of their cultural heritage, and it’s become popular for young girls to learn it again.

Yue-Qing Yang brought Nu Shu to national awareness with her documentary, Nu Shu: A Hidden Language of Women in China, and Lisa See’s novel Snow Flower and the Secret Fan (also now a film) is another vivid resource for learning about Nu Shu and the lives of the women who wrote it.

While there are only four women left who are fluent in Nu Shu—they use it now mainly to attract tourism to their villages—Nu Shu remains an astonishing landmark of the human spirit, a reminder that art and literature can flourish in even the most oppressive situations.While there are only four women left who are fluent in Nu Shu—they use it now mainly to attract tourism to their villages—Nu Shu remains an astonishing landmark of the human spirit, a reminder that art and literature can flourish in even the most oppressive situations. Can you think of any other languages that have survived despite the odds?