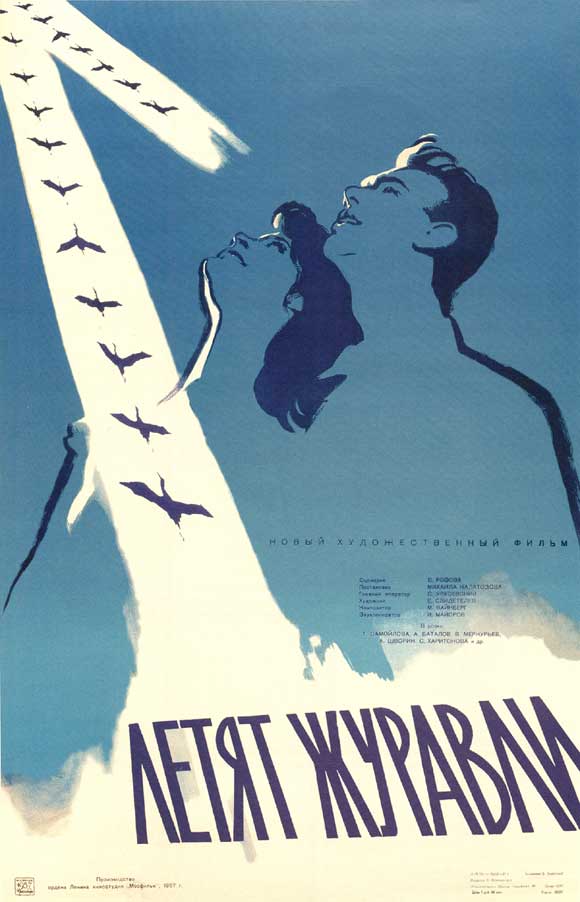

The Cranes are Flying (Летят Журавли) showed a complex and flawed character, whose supposed betrayal of her partner, a veteran of the Great Patriotic War (or World War II), was treated with a great deal of empathy. In many ways, this film symbolized the period of Soviet history between Stalin’s death and the invasion of Czechoslovakia, denominated as the Thaw. Director Mikhail Kalatozov started out as a radical, but was soon working within the Socialist Realist vein of Stalinist times. However, he managed to free himself in the 50s and 60s, making some surprisingly experimental films along with his cameraman Sergei Urusevsky.

"In many ways, this film symbolized the period of Soviet history between Stalin’s death and the invasion of Czechoslovakia, denominated as the Thaw."

The story centres around a doctor and his family, including his son Boris and his girlfriend, Veronika. Unbeknownst to Veronika, Boris is killed early in the war, while she is pursued by the doctor’s nephew, Mark. She eventually goes to live with the doctor’s family after her own family is killed during an air raid. There, Mark seemingly rapes Veronika, who is forced to become his wife, despite the guilt she feels in apparently abandoning Boris. Mark’s failings as a character are demonstrated by his dodging the army draft through underhand bribery, and he is thrown out of the home. Veronika, however, is forgiven, even if reluctantly by Boris’s sister. A surviving soldier tells Veronika about her boyfriend’s fate, but she refuses to believe him and only becomes convinced of his death at the end of the war. The film is not so radical in its plot – asides from the empathy shown to the female protagonist, who was seen by many critics as a real flesh-and-blood woman rather than an ideal Social-Realist construct – so much as in its cinematographic language. The final scene, as well as the moment when Veronika fails to find Boris among the group of soldiers leaving for war, generates especially emotional responses, precisely due to the strength of the film-making.

The movie was based on a play, and the language spoken is general educated Russian, with no special regional or dialectal divergences. There are, nonetheless, some interesting moments. Boris’s father mocks two komsomolki (members of the All-Union Leninist Young Communist League) with a parody of their officialese: “Resist until your last drop of blood, beat the fascists, and we at the factory will fulfil and over-fulfil the plan. Yes, we know all that. Better sit down and drink to my son Boris” (Держитесь, мол, до последней капли крови. Бейте проклятых фашистов, а мы на заводе будем выполнять и перевыполнять. Все это нам известно. Лучше садитесь, выпьем за моего сына Борьку).

Veronika, throughout the film, repeats some nonsense verses especially written for the film by the scriptwriter and playwright: “The cranes, little ships fly under the skies/ And the grey ones, the white ones, and those with long legs/ The froggy-quack quacks walked along the shore/ They all jumped, and scuttled off and gathered gnats” (Журавлики-кораблики летят под небесами. /И серые, и белые, и с длинными носами /Лягушечки-квакушечки по берегу гуляли /Все прыгали, да шмыгали, да мошек собирали).

"Finally, Soviet cinema had produced real, genuine characters, and not simple, mythical, positive fairy tale heroes."

There are a few other especially colourful terms. Mark is asked, “Куда ты прифрантился?” which translates as: “Where are you going dressed so flashily?” (although “прифрантиться” is a far more literary term than the English equivalent, “flashily”). Also, a term like “драпануть” (to depart in haste) is part of an interesting citation: “Сибирь... Вон куда мы драпанули, куда матушка Россия подалась” (Siberia … to where we all departed in haste, to where Mother Russia drew us). These terms, along with a few others, add some colour to the script and dialogue, though the film cannot be said to have transgressed linguistic norms.

The Cranes are Flying went on to win the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, garnering genuine international interest and adoration. It was felt that, finally, Soviet cinema had produced real, genuine characters, and not simple, mythical, positive fairy tale heroes.