Italy in the mid 1950s was full of contradictions and divisions, some as old as the Risorgimento itself and intensified during the years of Fascism and Cold War. There were cultural and social clashes, with every field of society split into two or more sides: Democrazia Cristiana versus the Communist Party, North versus South, alphabetization versus analphabetism, entrepreneurs versus workers. Even the language was cause for incomprehension. Dialects were still dominant and RAI, Italy’s national public broadcasting company, had only just begun its television service and had not yet created a nationwide linguistic common ground.

"The film is not exactly a masterpiece, especially the romantic bits, which are –frankly—forgetable"

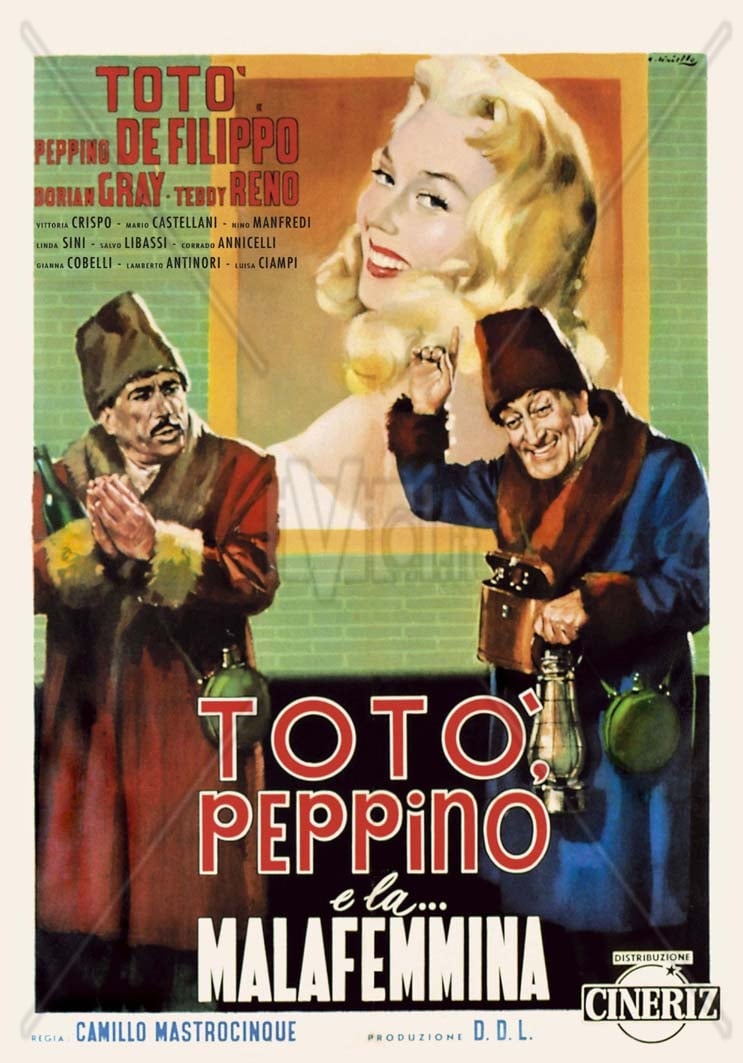

In 1956, Totò, the most popular comedian in Italian cinema, alongside Peppino De Filippo, by far his best right-hand man, starred in Totò, Peppino e la...malafemmina, by veteran director Camillo Mastrocinque. It was inspired by Totò’s most famous song, “ Malafemmena ,” a classic in the Neapolitan tradition. The plot is very thin: two brothers and farmers, Totò and Peppino, try to rescue their nephew, their sister’s son and a university student in Naples, from the dancer Marisa, the “ malafemmina ” of the title. This term means “prostitute” or “fickle woman” in the Neapolitan dialect, and in the story, she brings the young student to Milan, causing a big scandal and jeopardizing his reputation.

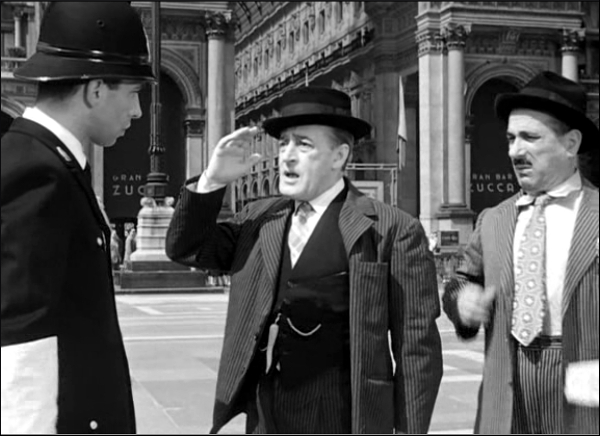

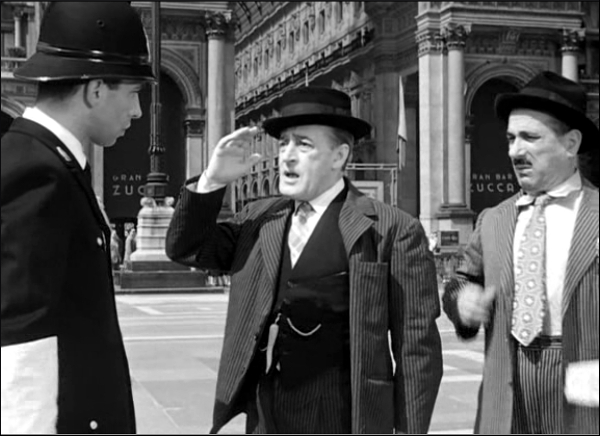

Totò’s and Peppino’s trip to Milan perfectly dramatizes some of the aforementioned contradictions, which are provoked mainly by clichés, ignorance, and the opposition between the present and the past. The Caponi brother arrive to the metropolis from their village near Naples dressed up as Cossacks because their neighbor, who had once been to Milan, had given them an unrealistic and mythological idea of Milan as a cold and foggy place, potentially dangerous for foreign visitors. Once there, the brothers also face a linguistic dilemma: what language should they speak? Unlike their nephew and Marisa, who represent the present and modernity, and who speak proper Italian, the Caponi brothers are ignorant and represent the past and traditions. They speak a form of Italian with a Neapolitan tint, seasoned once in a while with some attempts at higher language, such as misquoted Latin: “ Abbondandis in abbondandum . ”

At other times, like when he meets a traffic officer who speaks the Milanese dialect – “ Se ghé ?” (What’s up?) –, Totò comes up with a mixture of languages and dialects. “ Excuse me... bittescèn, noyo volevàn savuàr l'indiriss... ja ?” (Excuse me, please, we wanted to know the address... yes?) combines English, German, French, and Milanese. When Totò finds out the officer speaks Italian after all, he offers another linguistic rave: “ Per andare per dove dobbiamo andare... per dove dobbiamo andare ? Così: una semplice informazione !" (In order to go where we have to go... where should we go? Just that: a simple information!).

All of these mistakes and puns have become classics of Italian culture, widely-known and quoted in everyday life. However, the real shining moment of the film comes when Totò dictates a letter to Peppino, through which he hopes to convince the malafemmina to leave their nephew. The text of this letter has been referenced many times in later decades, particularly by Roberto Benigni and Massimo Troisi in their 1985 film Non ci resta che piangere. Puns, grammatical mistakes, misunderstandings, and more abound in this famous letter, which grows into an example of pure nonsense accompanied by incomparable acting and mimicry:

“ Signorina: veniamo noi con questa mia addirvi una parola che che che scusate se sono poche ma sette cento mila lire; noi ci fanno specie che questanno c’è stato una grande morìa delle vacche come voi ben sapete. Perché il giovanotto è studente che studia che si deve prendere una laura che deve tenere la testa al solito posto cioè sul collo. Salutandovi indistintamente i fratelli Caponi (che siamo noi i Fratelli Caponi) ” [Miss, we are coming to you with this mine in-order-to-tell-ya, a word that, that, that, forgive us but 700.000 liras; we they get us surprised for this year there has been a great blight of the cows as you very well know. For the youngman is a studying student who has to get himself a degree who has to keep his head in the usual place that is on the neck. Greeting you indistinctively the Caponi brothers (that we are the Caponi brothers) ] .

"Totò, Peppino e la...malafemmina manages to depict a country on the verge of change, the future and the economic boom about to arrive."

The film is not exactly a masterpiece, especially the romantic bits, which are –frankly—forgetable. But it soars whenever Totò and Peppino are in front of the camera, improvising their acts. Moreover, Totò, Peppino e la...malafemmina manages to depict a country on the verge of change, the future and the economic boom about to arrive.