The Punderful World of Paronomasia

Alfred Hitchcock once said, “Puns are the highest form of literature.” Far be it from me to challenge his literary tastes, but I have always found puns to be cringe-inducing. This is mainly because in college I had a writer friend who peppered his stories with the most egregious of puns. (Pirates with eye-patches would always be saying things like, “I’ll keep an eye out for you!” and the like.) He always insisted I wasn’t cultivated enough to appreciate his fine humor.

This is not entirely true. Once in a blue moon I’ll laugh at a pun. I laughed when someone told me to be careful eating maní, (South American Spanish for peanut,) because it could turn me into a maniac. The one moment I enjoyed in the otherwise horrendous fourth season of Arrested Development was Lucille Bluth commandeering a ship being referred to as “the seaward matriarch.” In general, I find puns funny when there’s a moment of searching for the joke, if it twists my expectations and delivers the punch-line in a surprising way. But there seems to be a very narrow window between the puns I find obvious and corny and the puns that go over my head and need to be explained to me before I get them.

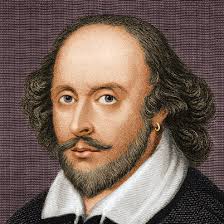

Of course, punning—the technical term is “paronomasia”—has a long and illustrious tradition in the literary world, with Shakespeare being notorious for throwing puns left and right into his plays to torment future students of 12th grade English classes. Romeo’s gloomy line from Romeo and Juliet, “You have dancing shoes/ with nimble soles; I have a soul of lead,” works through the use of homophones, or words that sound the same when spoken aloud. Another example of this would be George Carlin’s quip, “Atheism is a non-prophet institution.” There also exist homographic puns that work with words that have the same spelling but different meanings, such as Mercutio’s dying prediction, “Tomorrow you shall find me a grave man.”

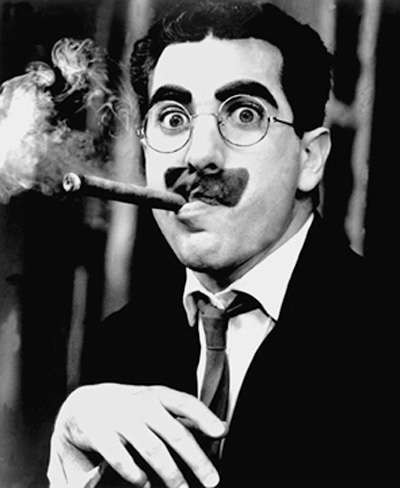

Notable writers and poets of the English language are also known for their prolific punning, such as John Donne, Alexander Pope, and Lewis Carroll. Vladimir Nabokov scarcely has a single character whose name isn’t a pun of some sort. In Lolita, the protagonist Humbert’s name is a reference to ombre, the French word for shadow, while pages are written on his obsessing over Lolita’s name, Dolores Haze. (Dolor is the Spanish word for pain, and a haze is what Humbert finds himself in whenever he’s near her.) James Joyce is also known for his fondness of puns and double entendres—Ulysses has the nonsensical until you read it out loud, “if you see kay,” poem while Finnegan’s Wake is virtually 700 pages of nonstop wordplay. Comedian Groucho Marx made his career out of puns like, “Heifer cow is better than none,” and, “I made a killing on Wall Street a few years ago. I shot my broker.”

Although my opinion of puns still coincides with that of Samuel Johnson, who viewed them as the lowest form of humor, I have to admit they play an important role in language and literature. My friend, who is currently working on his PhD, still sneaks puns into drafts of his thesis to amuse himself during long hours of writing. Academics do this all the time, he assures me, and of course puns are rife in music, television, and advertising, so there’s no way of escaping them.

Do you have any good puns you’d like to share?