- The House of Bernarda Alba

- Published by: Editorial Losada

- Level: Beginner

- First Published in: 1945

When a repressive and authoritarian matriarch becomes a widow, her five daughters are forced to mourn and stay home for eight years. But the young women envision a different fate for themselves.

La casa de Bernarda Alba (The House of Bernarda Alba) is a theatre play written by the poet Federico García Lorca. It was published in 1936, the same year as the beginning of Franco’s dictatorship. It represents an Andalusian family and a suffocated society surrounded by religious customs. (Andalusia is not mentioned, but it can be deduced as the setting because of the style of the town and the houses, as well as the origin of the writer.) Bernarda is a repressive and violent woman, who has just become a widow and has to support her five daughters (the oldest from a former marriage). After her husband’s death, Bernarda forces the daughters to mourn for eight years, during which they are not allowed to go out, and have the sole task of embroidering their trousseau. Because all of them are single (with the exception of the oldest one, who has a boyfriend) and are old enough to get married, several unpleasant situations take place amidst an atmosphere of jealousy and betrayal that only comes to an end when tragedy occurs.

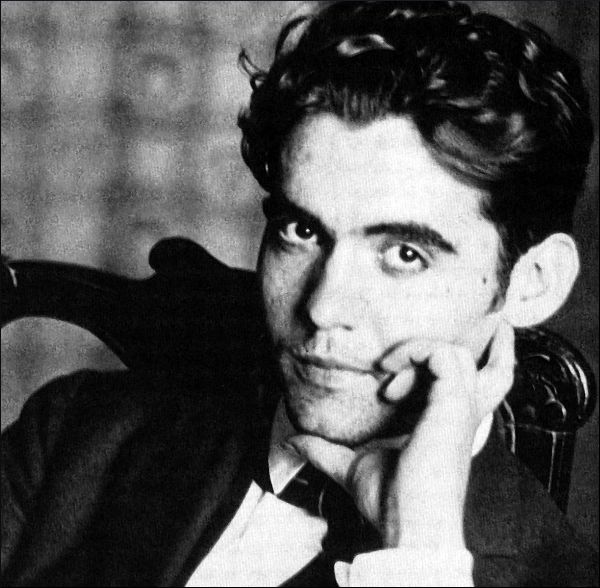

Federico García Lorca always liked to write plays focused on the plight of women in the oppressive context of his time. Because he was a republican (a left-wing supporter), he enjoyed criticizing the shameful side of society. The topic of suffering women was particularly productive for him, since he was brought up and lived surrounded by women. He had a brilliant career, until he was shot by right-wing soldiers, literally because “he was republican and gay.” The House of Bernarda Alba is a nightmare from the deepest Spain, in a time when women had a secondary role and the only thing they were able to do was stay silent and obey.

"It represents an Andalusian family and a suffocated society surrounded by religious customs."

When Bernarda's husband dies, she takes the lead inside the house, acting as the matriarch. Raised in a very conservative way, Bernarda forces her daughters to dress in black, remain locked in for eight years, sacrifice their youth, forego having a boyfriend, and be “decent people” according to her severe dogma, so that no neighbor can say bad things about them. In such a repressive atmosphere, women’s honor was taken very seriously, and they had to take special care as to how they were dressed, avoiding joyful colors or the use of make-up, and speak only when they were requested to. Religious customs are also very evident. For example, the bells are tolled twice when there is a funeral, the dead person’s clothes are stored in a trunk, black mourning clothes and veils are worn in church, and so on. There is also an aversion to intimacy, as shown when the daughters have to take a bath with their clothes on.

Being a woman at that time was indeed a tragedy, and the girls’ desperation to have a boyfriend has to do with the fact that the only way to leave the family house was by getting married. So they all want to have something that they are not really sure they want to have. “Damn all the women,” says one of the daughters at some point in the play. “I don’t know whether having a boyfriend is good or bad,” says another sister, to whom a third replies: “It’s all the same.” The girls regard men as something mysterious and a little bit violent, because they see them “beating the donkeys.” Men are something unknown to them, as the sisters are isolated and only surrounded by other women. When the oldest daughter realizes that her boyfriend is very serious and quiet, she asks him what the problem is and he replies: “Men’s stuff.” As if a woman were unable to understand it, as if they were worlds apart.

Among the Spanish customs of the time, it is interesting to highlight the style of the houses, big and spacious, with an external central patio and very white walls (like Andalusian houses), a chicken coop, and a pantry where vegetables or meats are stored for the winter. It is also possible to guess the poverty of the era, as a servant asks the housekeeper for some food for her daughter when Bernarda is not home.

"Federico García Lorca always liked to write plays focused on the plight of women in the oppressive context of his time."

The language used by the characters is neutral Castilian, although there are some words typical of small towns, like for example “gañán” (silly, rogue) or “forastero” (stranger, somebody from the next town). Moreover, there are the typical nicknames used in small towns, such as Pepe the Roman, Paca the Roseta, and La Poncia, among others. It is interesting to mention that we observe the action from the women's perspective, which means that we never hear the words said by Pepe the Roman (the oldest daughter’s boyfriend) nor do we see him as a physical figure. What we know about what he does or says, we know it because the girls say it. This is another way to make the reader feel estranged from the masculine world.

The House of Bernarda Alba was made into a movie in 1987, directed by Mario Camus. It’s quite well-adapted, following the book line by line. There are a bunch of famous Spanish actresses in the movie, including Florinda Chico in the role of Poncia and Ana Belén in the role of Adela. Especially remarkable is the performance of Irene Gutiérrez Caba, who plays Bernarda in a terrific way.