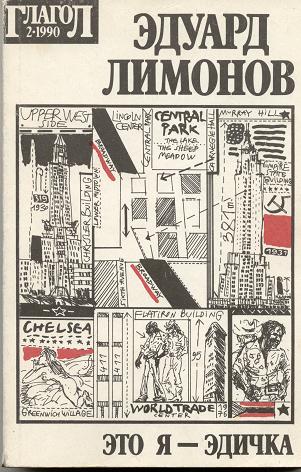

- It's Me, Eddie

- Published by: Random House (1983 English translation)

- Level: Advanced

- First Published in: 1979

Controversial Russian author Eduard Limonov writes about his experience as an exile living in New York City during the 1970s. A profane and iconoclastic semi-autobiographical novel portraying the less glamorous side of America.

Eduard Limonov’s Эта я- Эдичка (It's Me, Eddie) is one of the most important books to come out of the final wave of Russian émigré writers who fled Brezhnev’s Soviet Union. Yet Limonov’s vision was unique. A dissident amongst dissidents, his jaundiced view of American society and his fellow émigrés, as well as his contempt for the idea of stylistic purity, made him an isolated figure. Even today, Limonov remains a controversial figure, regularly arrested for his anti-government activities and occasionally imprisoned. He has swung from the far right to the far left. Only very occasionally has he risen to the literary heights of his early novels, and in recent times, he has abandoned writing novels for essays.

"One of the most important books to come out of the final wave of Russian émigré writers who fled Brezhnev’s Soviet Union."

This autobiographical or confessional novel sees the title character arrive in America with his wife Elena. While their relationship is initially passionate, Elena slowly abandons Eddie as she tires of the poverty of émigré life and searches for new and often richer lovers. The book concentrates mainly on Eddie’s life, surviving on welfare benefits and low-skilled, low-esteem jobs, such as being a busboy. The descriptions point to an America few Russian émigré authors wished to write about: that of the outcasts and of the racial and political minorities, the America of punk culture and radical politics. It also describes Eddie’s sexual odyssey, recounting his bisexual encounters amongst the marginalized layers of American society. It was a book that was intended to scandalize both nostalgic and conservative Russian émigrés in America as well as the mainstream American public. It pulled no punches.

At the very start of the novel, Limonov issues Americans this defiant statement: “Я получаю Вэлфер (…) Я считаю, что я подонок, отброс общества, нет во мне стыда и совести, потому она меня и не мучит, и работу я искать не собираюсь, я хочу получать ваши деньги до конца дней своих. (…) Не хотите платить. А на хуя Вы меня вызвали, выманили сюда из России, вместе с толпой евреев?” (I receive Welfare (…) I see that I’m a douchebag, a social misfit. I don’t have any shame or conscience, so it doesn't torment me, and I've no intention of looking for work. I want to receive your money till the end of my days (…) You don't want to pay. Well, then, why the fuck did you get me to come here, me along with a whole crowd of Jews?)

In many ways, this opening sets the deliberately scandalous tone of the book and emphasizes its stylistic properties. Eddie is as sincere an outsider in American society as Holden Caulfield, the protagonist of J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. Moreover, his style was as provocative to his fellow émigrés as was his tone and message. Limonov broke strong literary taboos as much as political ones, using Anglicisms, like “Вэлфер” or “welfer” (welfare), and even distorting Russian syntax, infecting it with a more English-like word order. He was also one of the first 20th century Russian writers to liberally sprinkle his works with Russian Мат (swearwords). For example, he uses all inflections and variations of the main swearwords, at times launching into трехэтажный мат, or strings of obscenities, literally “three-story obscenities” in Russian.

"Eddie is as sincere an outsider in American society as Holden Caulfield, the protagonist of J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye."

In the following passage, describing his experiences as a “Басбой” (busboy) – another Anglicism –, he turns one of the main three-letter nouns (equivalent to four-letter words in English), хуй, into a verb, хуячить: “И когда я покинул Хилтон, когда я в последний день хуячил с работы, я смеялся, как глупый ребенок” (And I left the Hilton. When I shag-assed out of work the last day, I laughed like a silly baby). Limonov’s was able to forge a new language and vision, mixing Russian and English and giving voice to the marginalized outsider, who no longer cares about any sort of propriety and who runs riot with acceptable literary standards. Some of his works, including this one, have earned him the kind of place in Russian literature that French and English letters reserve for Céline and Salinger, respectively.