Nadsat’s proper horrorshow

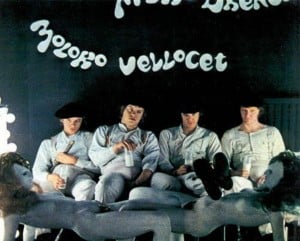

Anthony Burgess’ novel A Clockwork Orange is perhaps most famous in popular culture for the 1971 Stanley Kubrick movie adaptation starring Malcolm McDowell. While it was toned down in the movie to aid the audience’s understanding, the book puts more focus on Nadsat, a constructed language invented by Burgess to give more depth to the England that he created in the novel. Since the events of the novel took place in the future, Burgess wanted to create slang that would not sound dated to people reading it later on, but an added bonus is the unique type of narrative it creates.

Anthony Burgess’ novel A Clockwork Orange is perhaps most famous in popular culture for the 1971 Stanley Kubrick movie adaptation starring Malcolm McDowell. While it was toned down in the movie to aid the audience’s understanding, the book puts more focus on Nadsat, a constructed language invented by Burgess to give more depth to the England that he created in the novel. Since the events of the novel took place in the future, Burgess wanted to create slang that would not sound dated to people reading it later on, but an added bonus is the unique type of narrative it creates.

In fact, Nadsat isn’t a language, but more of a vernacular or argot – it’s essentially English with enough slang to render it difficult to understand for the uninitiated. Burgess was a keen linguist and polyglot, and his love for languages shines through in the dialect he created for his teenage characters. The protagonist of the story, Alex, writes in the first person and Nadsat is used throughout the book – both in descriptive passages as well as direct speech – so readers have to familiarize themselves with it if they want to understand the events of the novel (though in most editions there is a helpful glossary in the back!).

Nadsat is a strange mixture of Cockney rhyming slang and Russian (the name Nadsat comes from the Russian suffix for ‘-teen’: -надцать, [-nadtsat]). However, Burgess didn’t stop there – he used a wide variety of methods to create words and flesh out Nadsat.

For the majority of Nadsat words, Burgess took the Russian word and Anglicized it (i.e. made it look and sound more English). Often, an English homophone (a word that sounds the same but has a different meaning) for the Russian word is used instead.

Here are some examples of Nadsat terms formed from Russian words:

- raskazz – story (from рассказ rasskáz, meaning ‘story’)

- veck – a man, or person (from человек čelovék, meaning ‘man’, shortened form)

- lewdies – people (from люди, ljúdi, meaning ‘people’, Anglicized)

- gulliver – head (from голова golová, meaning ‘head’, homophone)

- horrorshow – good (from хорошо khorosho, meaning ‘good’, homophone)

Some words are formed from Cockney rhyming slang, but with an extra twist to disguise their real meaning even further. For example, cutter means ‘money’ (from ‘bread and butter’), and hound-and-horny means ‘corny’.

There are also terms derived in other ways – existing words were shortened (e.g. cancer means ‘cigarette’, a shortened form of ‘cancer stick’), or sometimes lengthened – often in a juvenile way (e.g. appy polly loggy means ‘apology’; skolliwoll means ‘school’).

Some words were formed from onomatopoeia (e.g. tick-tocker means ‘heart’; boohoohoo means ‘to cry’).

There are also portmanteaus – words formed from combining two other words (e.g. chumble means ‘to mumble’, from ‘chatter’ and ‘mumble’; crark means ‘to howl’, from ‘crow’ and ‘bark’; and the infamous word ultraviolence means a particularly despicable or violent act).

There is also plenty of English slang, used both directly and indirectly (e.g. sarky meaning ‘sarcastic’; warbles means ‘songs’, as in the English word ‘to warble’ meaning ‘to sing’). There is also plenty of invented slang from existing words, such as sinny for ‘cinema’, or vaysay meaning ‘toilet’, from the French pronunciation for ‘W.C.’.

It’s interesting to note that Nadsat isn’t what made A Clockwork Orange the cult classic that it is today – many people remember the novel and the movie best for its portrayal of strong adult themes (mainly violent and sexual crime), and the highly disturbing nature of Alex’s punishment. However, it is a fascinating novel to read, especially for those interested in languages and linguistics.

For more information, you can find a full list of all the Nadsat used in A Clockwork Orange here.